Foundations of a functionalist

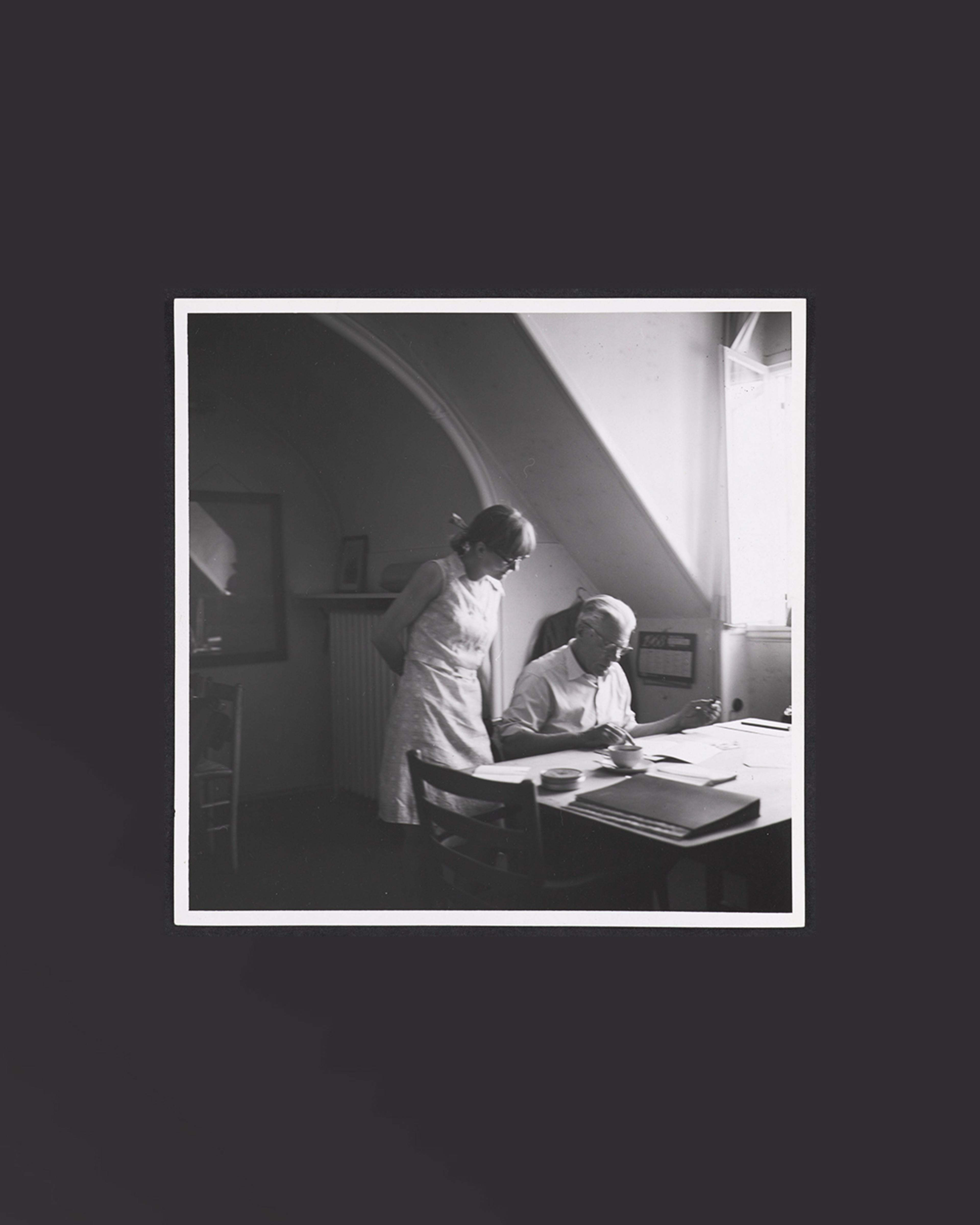

Beneath the eaves of Kunsthal Charlottenborg – formerly home of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts – Mogens Koch subtly shaped the future of Danish architecture and design. As a professor, craftsman, and devoted functionalist, he spent nearly two decades nurturing a philosophy of simplicity, precision, and preservation. His office, brimming with drawings, books, and precisely chosen materials, mirrored both his deep engagement and the years he spent refining his craft.

Koch’s approach to architecture and furniture design was firmly grounded in the principles of Danish functionalism. He believed every element should serve a clear purpose, with form naturally emerging from function.

His foundational principles were shaped through collaborations with key figures such as Carl Petersen, Ivar Bentsen, and Kaare Klint, with whom he worked closely in their studios. Klint's advocacy for simplicity and standardised solutions made a lasting impression, significantly influencing Koch’s own functionalist philosophy.

Koch’s work was defined by meticulous attention to detail. The quiet, systematic refinement of even the smallest element seemed both his greatest challenge and joy. For him, a project was truly successful when a complex problem was resolved in the simplest possible way – so seamlessly that the underlying complexity disappeared. His process always began on a squared sketchpad, where he developed everything from tables and bookcases to entire interiors, even church organs. Koch himself once said, with characteristic modesty: ‘It’s so wonderfully easy on a squared sketchpad, where you have units of measurement – and you can do it while drinking tea.’ Although his work spanned various disciplines, each piece reflected his devotion to precision and functionality.

“ It’s so wonderfully easy on a squared sketchpad, where you have units of measurement – and you can do it while drinking tea. ”

Mogens Koch, on his devotion to precision and functionality

Preserving the past, shaping the present

As an architect, Koch played a pivotal role in restoring historic buildings across Denmark. Early in his career, between 1925 and 1930, he worked under Kaare Klint on the restoration of Frederiks Hospital, which is now home to Design Museum Danmark. He later assumed significant responsibilities, including serving as the architect for Roskilde Cathedral. He also contributed to restoration projects abroad and designed several summer cabins.

The precision evident in his buildings carried through to every joint, curve, and surface of his furniture. But Koch’s contributions transcended physical environments – they reached into the realm of thought, education, and critique.

Though he rarely published his views, Koch authored one of his few articles in 1938, Restoration (org. Restaurering), which appeared in the architectural journal The Architect (org. Arkitekten). In the article he criticised prevailing restoration practices, which he considered destructive rather than preservative. He rejected reconstructions and refurbishments that blurred the line between old and new, urging that buildings should retain visible signs of their age and history. For Koch, a building's age should not be erased but acknowledged – its patina an essential part of its truth. This rare piece of writing remains essential to understanding his philosophy – both as a practitioner and as a professor. His ideas took on a more tangible form two decades later, when he spearheaded Denmark’s first formal education programme in Architectural Restoration at the Royal Danish Academy - Architecture, Design, Conservation.

A Living School of Thought

For the first time, students could pursue a dedicated course in the care and preservation of historic architecture. At the time, restoration was neither a celebrated career path nor a particularly popular academic field. Yet, Koch’s vision helped shift that perception. What began as a niche discipline became central to safeguarding Denmark’s architectural heritage – and the programme he helped establish continues to shape experts in the field today.

Koch’s legacy endures in the halls of the Academy. Architect Christoffer Harlang, his successor, notes how Koch’s work responded to the needs of post-war Europe and highlighted the growing importance of historic architecture.

“When Mogens Koch took on his professorship, the Second World War had only recently ended, leaving Europe with devastated cities and monuments. This sparked an urgent need to rebuild and restore cities, as architecture plays a vital role in our identity and self-understanding. Koch was deeply engaged in this process, recognising the aesthetic potential of historic architecture while continuously seeking ways to adapt it to his own time.”

While Koch made a lasting mark through his contributions to architectural restoration, his work on furniture design holds an equally enduring place in design history. As architecture historian Michael Sheridan notes: “His underlying ambition as a furniture designer was to create very simple models of extremely functional furniture that could be used in many settings for a lifetime, or longer. To that end, he studied the furnishings of ancient Egypt, Renaissance Italy and Georgian England. As a result, each of Koch’s furniture designs has the character of an archetype: an ideal version of a historical model that incorporates lessons from earlier examples and has been distilled to its essential form. Because those archetypes are defined by their use and devoid of stylistic cues, they remain contemporary in every era.”

For Koch, furniture was never merely decorative. Each piece of furniture he designed reflected careful historical and mathematical proportions and a thoughtful balance of function and form, mirroring the precision of his architectural work.

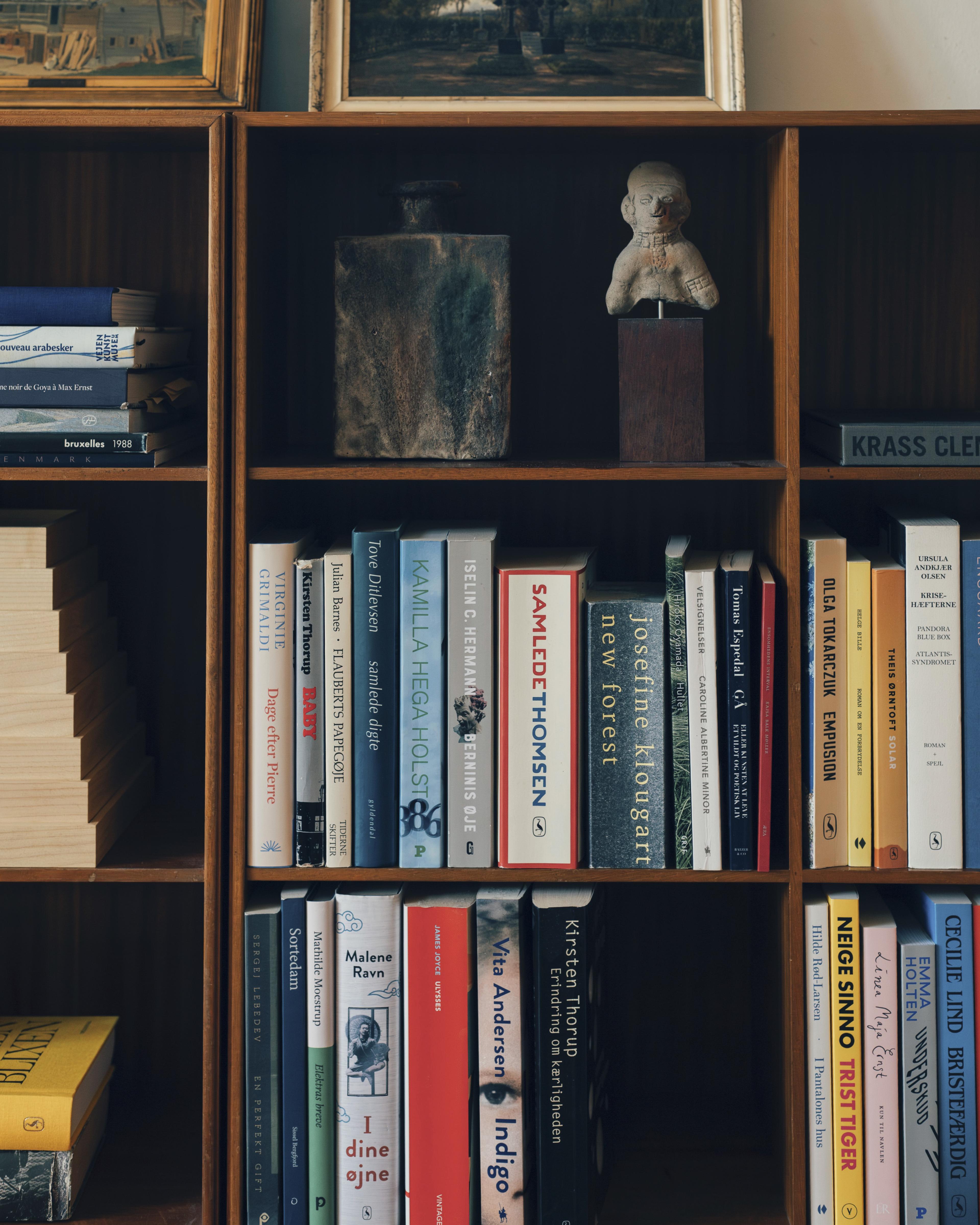

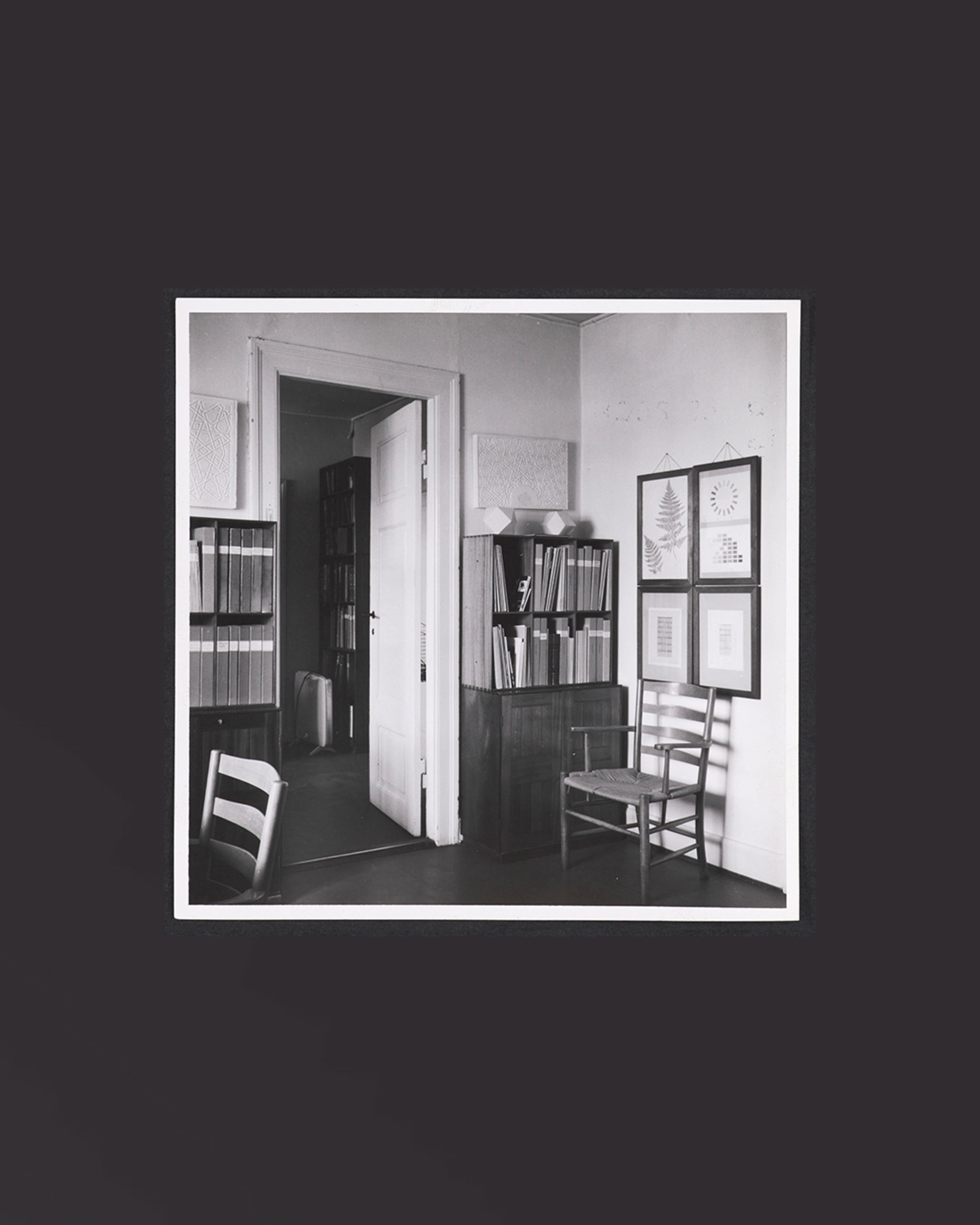

A studio that still breathes

Looking back at the pictures of Koch’s office from 1968, you spot a quiet tribute to Kaare Klint’s design philosophy. Many of the furniture pieces are linked to Klint either directly or through his students. Koch’s own bookcases, based on Klint’s functionalist principles, line the walls. Around the room sit Børge Mogensen’s J39 chairs, designed by another of Klint’s protégés. Even Klint’s own masterpiece – the Klint Chair – holds a place of honour, a silent testament to a school of thought that shaped an entire generation.

Even today, elements from Koch’s continue to serve a purpose at the Royal Danish Academy - Architecture, Design & Conservation. Architect Christoffer Harlang now works among furniture once selected by Koch himself. Reflecting on their enduring presence, he observes: “The Klint Chairs have accommodated four generations of professors – including Mogens Koch, Vilhelm Wohlert, Hans Munk Hansen, and now me. Several pieces of furniture in our offices, designed by Børge Mogensen, Mogens Koch and Poul Kjærholm, have all remained integral to the institution since the 1950s.”

To step into the Academy today is to experience a space not merely furnished by Koch but formed by him – a living archive of ideas defined by clarity, humility and purpose. His legacy lingers not only in objects and spaces, but in the quiet rigour of minds still guided by his measured hand.

Keep exploring

Through a series of narratives, we explore inspiring spaces, delve into architectural history topics, explore the essence of good design, and celebrate the cultivation of unique atmospheres.

1 of 4